The world of wine, steeped in tradition and bound to the land, is facing an unprecedented challenge: climate change. From scorching wildfires in California to unexpected frosts in Spain, the delicate balance that allows vineyards to thrive is being disrupted, forcing winemakers to adapt and innovate in ways previously unimaginable. This article explores how the wine industry, a sector deeply connected to specific regions and their unique climates, is responding to the escalating impacts of a changing world, showcasing the resilience and creativity that are emerging as vital tools for survival. The keyword Climate Change Is Forcing the Wine Industry to Get Creative is essential to understanding this evolution.

A Hazy Reality: Wildfires and the Harvest

The story of modern winemaking is increasingly intertwined with the harsh realities of climate change. Take, for example, the experience of Bertus Van Zyl, a winemaker at Tank Garage Winery. On a summer weekend, amidst hazy skies, he journeyed to California’s El Dorado County. His mission? To harvest Chenin Blanc, Picpoul, and Fiano grapes. While a refractometer, used to measure sugar levels, is typically a winemaker’s go-to tool, Van Zyl’s most crucial piece of equipment was an N95 face mask. This was to protect his lungs from the pervasive smoke and ash emanating from the Caldor wildfire, a raging inferno situated uncomfortably close to South Lake Tahoe. This highlights the challenges that Climate Change Is Forcing the Wine Industry to Get Creative to overcome.

This scene, once an anomaly, is becoming increasingly commonplace. Winemakers have always shared tales of challenging vintages – a sudden spring frost nipping at tender buds or a damaging rainstorm just before harvest. However, these stories are evolving. Chris Christensen of Bodkin Wines in Healdsburg, North Sonoma County, observes that "things that were legendary are now quite commonplace." He admits to picking grapes near active fires or facing the serious threat of smoke exposure to his grapes since 2015. To mitigate the risk, Christensen is strategically sourcing grapes from three different counties, ensuring that a single fire cannot decimate his entire vintage.

A Global Struggle: Extreme Weather and Shifting Landscapes

The challenges faced by winemakers are not confined to California. Wineries worldwide are grappling with extreme temperatures, water shortages, and altered grape ripening patterns. Climate experts emphasize that this "new normal" demands flexibility and innovation from the wine industry as the climate continues to change.

Bertus Van Zyl and his wife Allison, founders of Belong Wine Co., were mindful of potential wildfire risks when selecting vineyard locations. They chose Mourvedre vineyards at elevations between 2,000 and 3,000 feet, aiming for a cooler, alpine climate with snowfall. They also opted for north-facing vineyards to shield the vines from intense sunlight. Despite these precautions, their grapes have not been entirely immune to wildfire smoke. Smoke-tainted grapes can impart an undesirable "campfire on an ashtray" flavor to the wine. "You can do everything right and then try to set yourself up for success, but there are consequences of the changing climate," Bertus Van Zyl laments.

Greg Jones, a climatologist based in Oregon, characterizes climate change as a subtle, slow-moving natural disaster, unlike abrupt events such as earthquakes or tsunamis. He points to historical examples to illustrate its gradual yet profound impact. Sixty years ago, England was considered too cold and wet to produce high-quality sparkling wine, and Oregon’s Willamette Valley struggled to consistently ripen Pinot Noir grapes. Today, however, English producers like Nyetimber and Ridgeview are crafting sparkling wines that rival Champagne, while the Willamette Valley has become a premier U.S. region for cool-climate Pinot Noir.

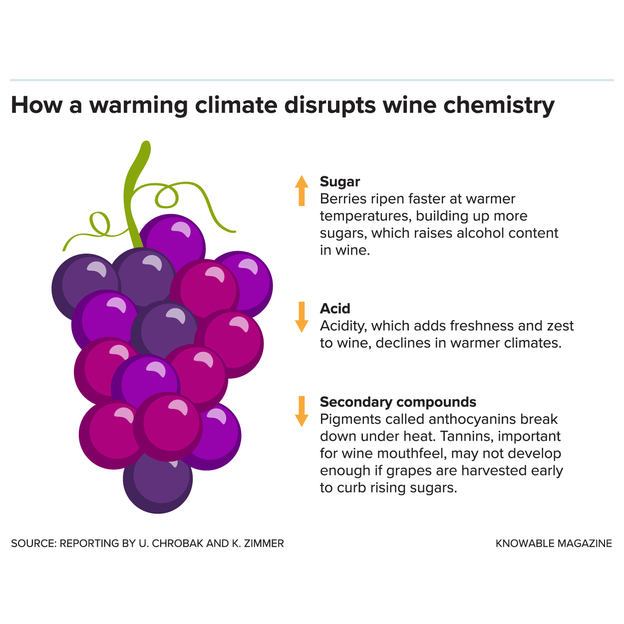

The delicate nature of Pinot Noir grapes, thriving within a narrow temperature range, underscores the impact of even slight climate shifts. Grapes with less sun exposure have lower sugar content, resulting in wines with brighter acidity and lower alcohol content. Warmer regions produce riper grapes, leading to more lush wines with higher alcohol content. Jones predicts that a 3 to 4-degree Fahrenheit warming over the next 50 years could alter the style of Pinot Noir associated with specific regions. "The Willamette Valley can still do Pinot Noir, but it’s going to be bigger and bolder with darker fruit characteristics," he explains.

In Ribera del Duero, a region in northwest Spain celebrated for its supple Tempranillo wines, increased sunlight is driving up alcohol levels. On Bodegas Viña Vilano wine labels from the 1990s, the alcohol content ranged from 12.5 to 13.5 percent. Now, according to export manager Pavlo Skokomnyy, it averages 14.5 to 15 percent. "What can we do?" he asks. "We need to find solutions to look for another grape or another kind of wine category." In Southern Spain, some producers are transforming extra-ripe grapes into sweet wines or substituting Tempranillo with Garnacha vines, which are better adapted to heat. The keyword Climate Change Is Forcing the Wine Industry to Get Creative is key to understanding this shift.

The arid Ribera del Duero region has faced even more severe climate-related challenges. In 2017, a surprise May frost decimated over 60 percent of the crop. As a result, winemakers decided to forgo the production of some younger Tempranillo wines to ensure sufficient fruit for their renowned age-worthy reserve wines.

Across California, wineries are grappling with droughts. Many embrace eco-friendly dry farming techniques, encouraging vines to develop deep roots in search of water. However, prolonged periods of drought can take a toll on the vines. In Sonoma, districts are implementing watering restrictions precisely when parched vines need water most. "That definitely affects the vines’ ability to get the fruit ripe, especially for late-ripening varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot," says Christensen, pushing winemakers to harvest earlier when the fruit has not reached its full potential.

In Anderson Valley, about two hours north of San Francisco, the 2014 vintage saw winemakers endure 350 days without rain between harvests, according to Guy Pacurar of Fathers + Daughters Cellars. Chronically thirsty grapevines produce less fruit. "The yield was down slightly from last year, but there is great intensity in the fruit," Pacurar notes. Droughts also result in smaller grape clusters, reducing the overall wine production. As the family replants older vines, they plan to incorporate hardier rootstock that requires less water.

The traditional seasonal rhythms that have guided farmers for generations are also changing. Typically, Anderson Valley grapes ripen from the south end in Boonville to the north, referred to as the Deep End by locals. "Two or three years ago was a weird instance where the entire valley ripened at the same time," Pacurar recalls. "They didn’t have enough vineyard workers, so some vineyards went unpicked."

Resilience and Innovation: Adapting to a Changing World

Faced with these shifting conditions, winemakers are embracing resilience and innovation. This means exploring new grape varietals, adopting different winemaking techniques, and creating entirely new wines.

A fire led to a new wine for Betty Tamm, who runs Triple Oak Vineyard in Oregon’s Umpqua River Valley. "In 2020, we had a big fire 8 miles away, so we had ash and burned leaves falling on our Pinot Noir vineyard and heavy smoke," she explains. "You couldn’t see to read a book at noon. Pinot Noir is a thin-skinned grape that’s very sensitive, and it will suck up that smoke flavor."

Rather than risk producing smoke-tainted Pinot Noir, Triple Oak decided to make a Pinot Noir Rosé, which requires only brief skin contact to achieve the desired color and flavor. Their Winter Sunrise Rosé proved to be a successful gamble, earning a silver medal at the Oregon Wine Experience.

At Bodegas Vilano, Cabernet Sauvignon typically ripens after Tempranillo, according to Desi Sastre Gonzalez, the vineyard’s director-general. "But right now, we have vintages where the Cabernet Sauvignon matures at the same time as the Tempranillo," says Sastre Gonzalez. This unexpected convergence has enabled them to create a new blend of Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot grapes called Baraja, which has been in production since 2015. "We have more alcohol, but we are still preserving a nice acidity, good tannin structure, and color for the wine," he says.

The Van Zyls understand that the livelihoods of their grower Chuck Mansfield and the people who pick grapes depend on winemakers making wine. "It’s not sustainable to just say we’re not going to make wine in smoky years," said Bertus Van Zyl. While Mourvedre, a red Rhone varietal, was the couple’s original focus, they’ve pivoted to making more white wines, which are often harvested before fire season. They’re also producing more rosés using a technique called carbonic maceration. Instead of crushing the grapes and letting the juice soak with the skins, grape clusters are carefully and slowly fermented whole. This allows the wine to take on intense, fruity flavors while keeping the smoky skins out of the mix. Climate Change Is Forcing the Wine Industry to Get Creative and these are the ways it is adapting.

"We have these conversations like can we keep this going? What is this going to look like for us?" said Allison Van Zyl. "Resiliency is the word that comes to mind from 2017," her husband added. "You get to see what communities are made of when you go through these terrible times. In that sense, you have a lot to be grateful for."

In conclusion, the wine industry, a sector deeply rooted in tradition and place, is facing unprecedented challenges due to climate change. The stories of winemakers around the world highlight the need for adaptation and innovation. From mitigating the effects of wildfires to embracing new grape varietals and winemaking techniques, the industry is demonstrating its resilience in the face of a changing world. The future of wine will undoubtedly be shaped by the creative solutions that emerge as winemakers continue to navigate the complexities of a warming planet.